Season aired: Summer 2025

Number of episodes: 12

Watched on: Netflix

Translated by: Logan Lampkins

Genres: Horror, Supernatural, Drama, Romance

Thoughts: The Summer Hikaru Died aired perfectly in the summer season, and it was one of my most anticipated anime of the year. The original manga became a hit sensation overnight during the pandemic, when Mokumokuren-sensei posted snippets on social media, only to unexpectedly see the story go viral. The Summer Hikaru Died is an examination of monsters in our world, how we interpret those monsters, and how we interact with them. In a tiny, sleepy countryside town in Japan where lots of strange entities walk amongst the living unbeknownst to the people around them, Yoshiki, a quiet high school boy, finds his life changed forever when his childhood best friend, Hikaru, reveals that he is no longer the Hikaru he grew up with.

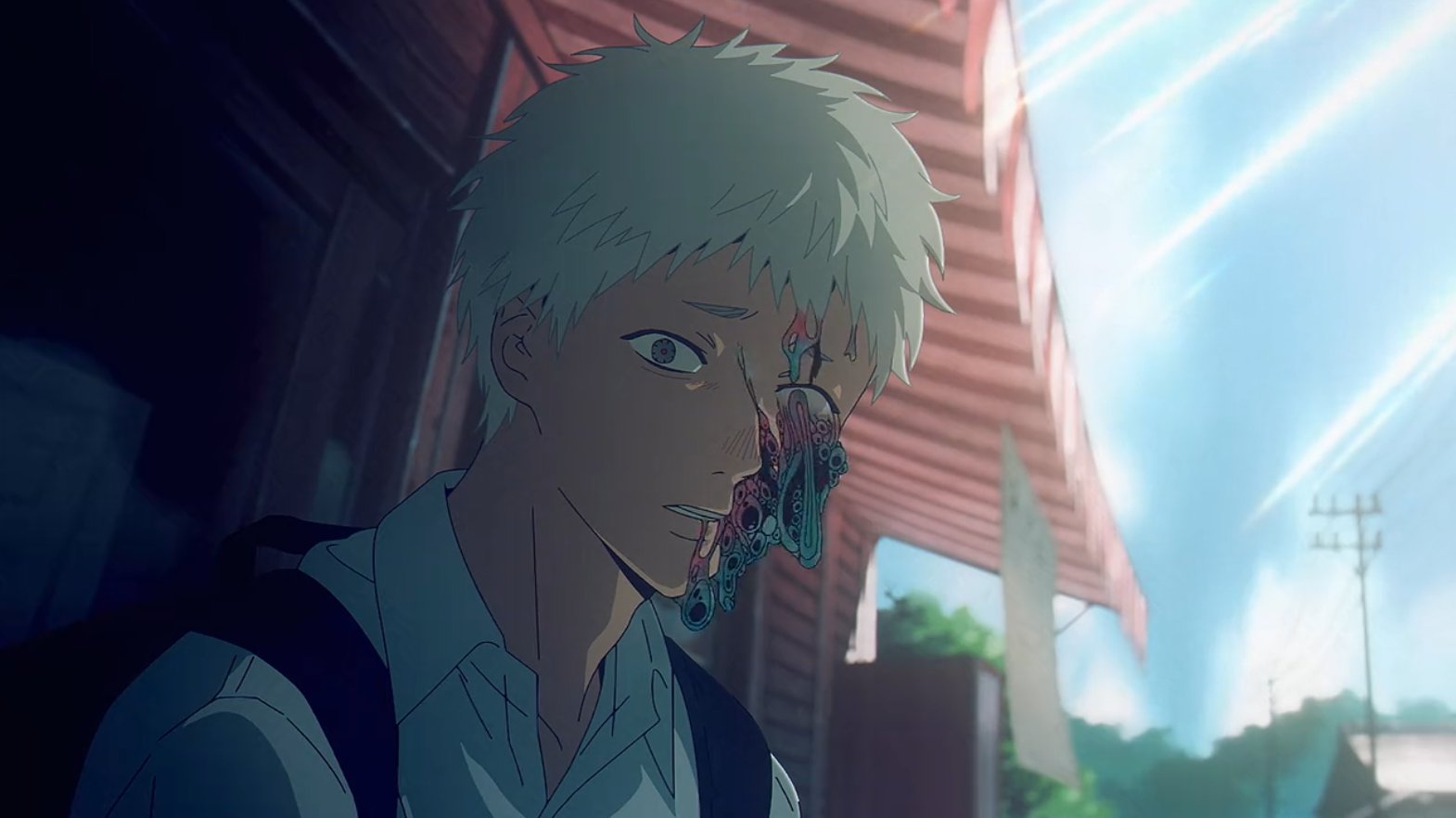

I am personally not a horror consumer, but not because of an overall dislike of the genre. I’m just a coward who gets scared easily and would rather keep my peace than interact with the genre on a normal basis. However, I have come to realize throughout the years that horror has resulted in some of the best stories, from classic novels to riveting movies to terrifying anime. One of the most famous scenes from The Summer Hikaru Died is when Yoshiki confronts “Hikaru” for the truth, and his best friend’s face suddenly leaks into a gooey, swirly mess. The visual image of that reveal was so electrifying that I pushed aside my cowardice to watch this show, and I can safely say that viewers like me who are scared of horror can safely consume this series. Because underneath all those scary headless supernatural creatures, deities who don’t understand the importance of death, and the concept of your best friend being replaced with something else entirely, The Summer Hikaru Died is actually a story about love for each other and yourself.

The plot of the series could be divided into two parts: the first part is Yoshiki coming to terms with Hikaru’s existence, and the second part is understanding what Hikaru actually is. The creature that possesses Hikaru’s human body retains no memories of its life before the possession, only that it lived in the mountains. This spurs Yoshiki to investigate his village’s history, leading to unique worldbuilding in a contemporary world. At one point, he lays out all the villages close to his, realizing that they form the figure of a human body, and Hikaru points out that they live in the “head” part of the formation. By that point in the series, the characters have faced several malicious, scary monsters, all of whom had warped heads, twisted necks, or were missing heads and necks entirely. While I originally saw those disfigured monsters as just something scary to fit the genre, the reveal of their village’s location instead becomes an exciting epiphany that the two patterns are interconnected. Throughout the show, various small details about the creatures they face could be dismissed as just “supernatural horror,” but I found it incredibly rewarding to learn that there is a greater connection to the world. It made me infinitely more interested in the story.

However, no matter the supernatural elements and mythology involved, The Summer Hikaru Died’s greatest strength is that it’s a deeply human story. Throughout history, monsters have been used to critique humankind and examine the deepest, dirtiest parts of human society. Whether it’s the willingness for humans to fall into mob mentality, the quickness with which humans assume the worst in the unknown, or the ease with which humans escalate to violence with a creature they never properly sought to understand, the story often ends by showing the irony: humans call a monster a “monster” when their own actions are far more heinous, monstrous, and terrifying than anything the creature has done.

The Summer Hikaru Died follows that same formula, but instead of focusing on Hikaru, it centers on the boy who desperately defends the “monster” that Hikaru claims to be. No matter how much bad-faith actors have tried to argue against it, this anime is a story about queer identity and how contemporary society has forced queer people to feel isolated, ostracized, and out of place. Yoshiki feels more aligned with “monsters” than the very people around him. This is a theme that the anime not only refused to water down but actually enhanced with creative and purposeful direction.

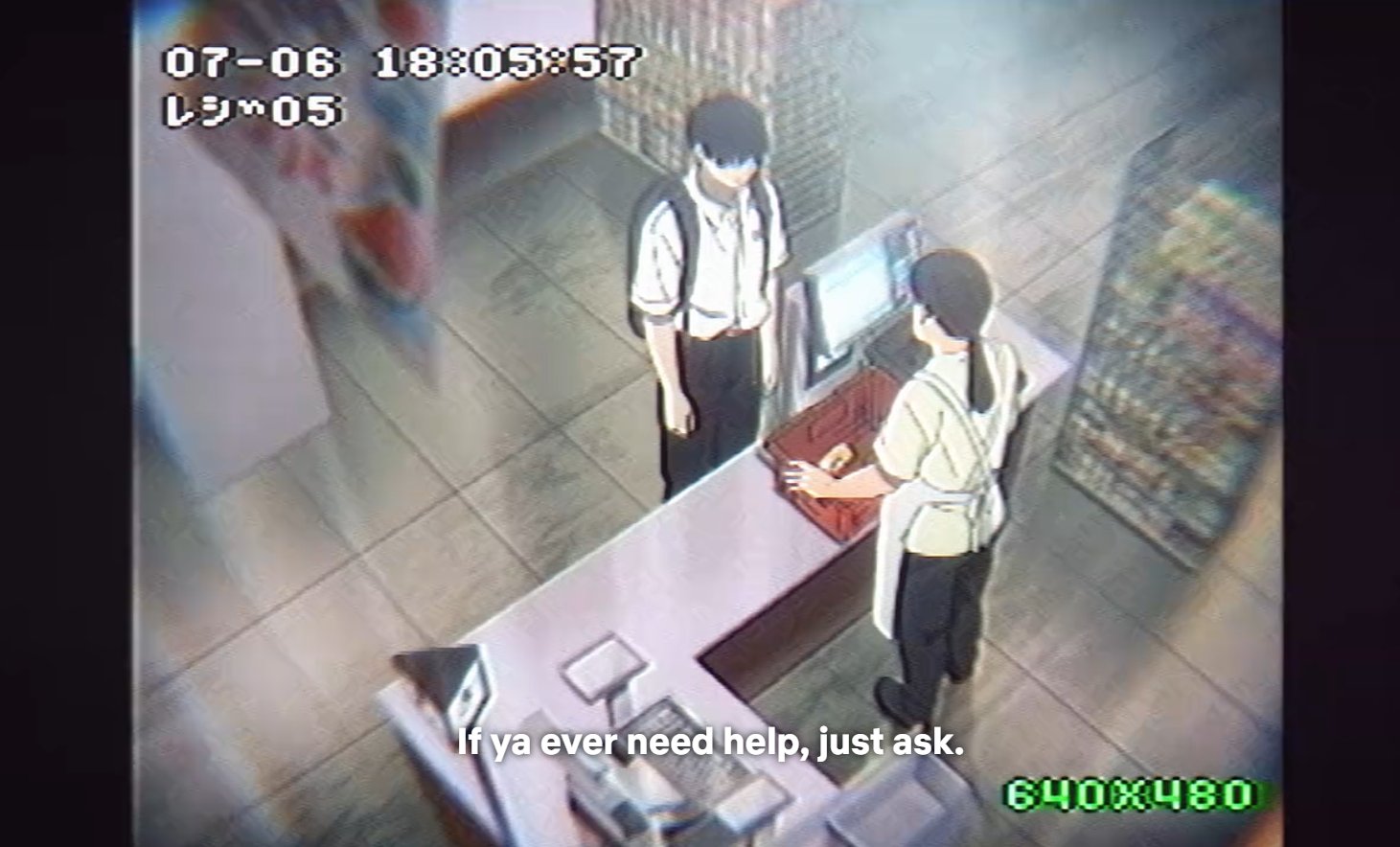

In the last episode, the two boys decide to go to the beach. Suddenly, they’re sitting in an actual train. The seats are photorealistic, the world passing outside the window looks like a live recording, and even the handles swing with the train’s movements. As Hikaru and Yoshiki talk about their respective places in the world, they remain in the anime art style, reflected in an actual mirror. They’re forced to be fictional in a real world that not only insists on but even enjoys rejecting their existences. Another scene that encapsulates this theme appears in the second episode, where a woman noisily grills Yoshiki about his home life. The scene switches from a normal POV shot of the two talking to a blurred, ominous CCTV — a horror of always feeling watched and always risking the secrets of the “monster” getting leaked to people around you. In an interview with Mokumokuren-sensei, the mangaka herself talked about how the protagonists are people “socially in the wrong” and how she had built her story around that.

On top of everything else, Chiaki Kobayashi shines as the complicated, grieving Yoshiki. He’s had a pretty good upswing in the last couple of years, snagging lead roles like Mashle from Mashle: Muscles & Magic, but of all the roles I’ve heard him in, Yoshiki is hands down his best. Not only is his commitment to the countryside accent commendable, but it’s in his silence and quiet tones that really convey Yoshiki’s complicated feelings towards himself and Hikaru. Shuichiro Umeda also does a fantastic job as Hikaru, voicing not only the monster possessing the human body but also the real-life Hikaru in Yoshiki’s flashbacks, sounding like two distinctive people with different personalities. I also want to give a shoutout to Chikahiro Kobayashi, who voices Tanaka, the antagonist of the first season. He absolutely sells the slimy, untrustworthy nature of this mysterious character.

When it comes to thematic explorations of the complicated human experience, no show does it better this season than The Summer Hikaru Died. At a time when the world is increasingly diving headfirst into humans repeating their heinous mistakes of the past in demonizing marginalized communities for no reason other than dissatisfaction with their own lives, this show affirms its love for all the “monsters” in the world. No matter how much of a monster people claim you to be, your feelings and your existence deserve to coexist with the world around you.

Rating

Plot: 8.5 (Multiplier 3)

Characters: 8.5 (Multiplier 3)

Art/Animation: 8.5 (Multiplier 2)

Voice acting: 9

Soundtrack: 8.5

FINAL SCORE: 85.5